BRITONS BE TRUE TO YOUR KING - EARL GREY (front)

BY TRAMPLING ON LIBERTY I LOST THE REINS - 1830 (back)

Taynton Metal Detecting Club

The Gannets

Earl Grey Political Medalet

BRITONS BE TRUE TO YOUR KING - EARL GREY

(front)

BY TRAMPLING ON LIBERTY I LOST THE REINS - 1830 (back)

A satirical medalet (counter) alluding to the downfall of the Duke of Wellington, who as prime minister, had opposed parliamentary reform. He was forced to resign in 1830, and was succeeded by Lord Grey.

The Great Reform Act

In 1815 England finally won the Napoleonic Wars which it had been involved in for twenty two years. The England of 1815 remained socially and politically the England of the 17th century. Despite the Industrial Revolution, which was rapidly changing the basis of Britain’s economic wealth from land to industry and trade, all the real power still remained in the hands of a territorial aristocracy numbering no more than a few thousand families. The system of government was a parliamentary monarchy and control of national policies lay in the hands of the two Houses of Parliament rather than the crown. The peers of the realm had hereditary seats in the House of Lords and together with the lords spiritual, they formed a solid bulwark not only against revolution, but also against reform. In local affairs they also wielded immense influence through their appointment to the magistracy and county administration. They controlled local justice and the administration of poor relief, ensuring a docile, even servile, rural population.

In theory the House of Commons, with members elected by the counties and boroughs, was a more representative body. However the right to vote and the right to election of a member rested on a property qualification which enfranchised a mere 150,000 out of a population of more than 15 million. In many ‘pocket’ and ‘rotten’ boroughs electors were sufficiently few for their votes to be bought and it was common practice for young wealthy men seeking a political career to buy a parliamentary seat for £5000 - £6000 Of the 658 seats in the Commons only about 50 were actually fought by rival candidates.

The privileged members of both Houses divided themselves between the two great parties Whigs and Tories. Both consisted of landowners equally devoted to the maintenance of the existing class structure and equally remote from the new centres of power that were beginning to reshape English society.

Vast new centres of population sprang up in the Midlands, Lancashire and Yorkshire as a result of industrialization which had made rapid progress during the wars, spurred on by the demand for guns, ammunition and army supplies. Along with the immense problems of accommodation, sanitation, local government and recreation, it also highlighted the inequalities and inadequacies of the parliamentary system which gave two seats to a ‘rotten’ borough, but denied representation to a great new city like Manchester.

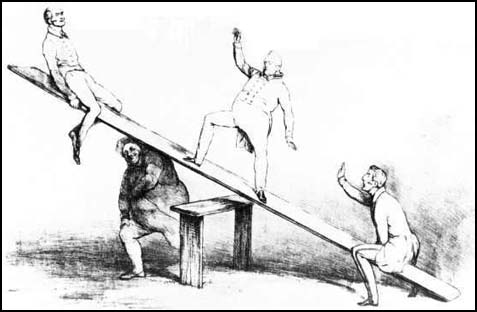

John Bull (public

opinion) helping Earl Grey against the Duke of Wellington and King William IV

by John

Doyle

The Tory party remained in office from the end of the war until 1830 first under Lord Liverpool and later under the Duke of Wellington. Their belief was that the British Constitution was perfect and that any attempt to disturb it must be put down firmly. However agitation for parliamentary reform was growing amongst the Whigs, the Radicals and some sections of the working classes. In 1830 the hated George 1V died and was succeeded by William IV, of no great intelligence though more amenable. In the summer and autumn of that year, a wave of riots (the Swing Riots) swept the country. Wellington stuck to the Tory policy of no reform and no expansion of the franchise, and as a result lost a vote of no confidence on 15 November 1830. In the general election of 1830 the Whigs were returned to power under Lord Grey. They immediately introduced a measure for parliamentary reform which passed into law in 1832 and is always known as the ‘Great Reform Bill’. Manchester and Birmingham for the first time received their own members of parliament, and the franchise was extended to householders in the towns rated at £10 a year and to £50 a year tenant farmers in the country. The electorate was thus increased to 600,000 voters.

The Act did not enfranchise the working classes, nor make voting secret. Parliamentary participation was still to rest on the possession of property as an indication of worth and responsibility. The Reform Act in no way converted the government into a democracy, though it was the first and in some ways the most decisive step in that process.

Find and write up by Mary Mayes.